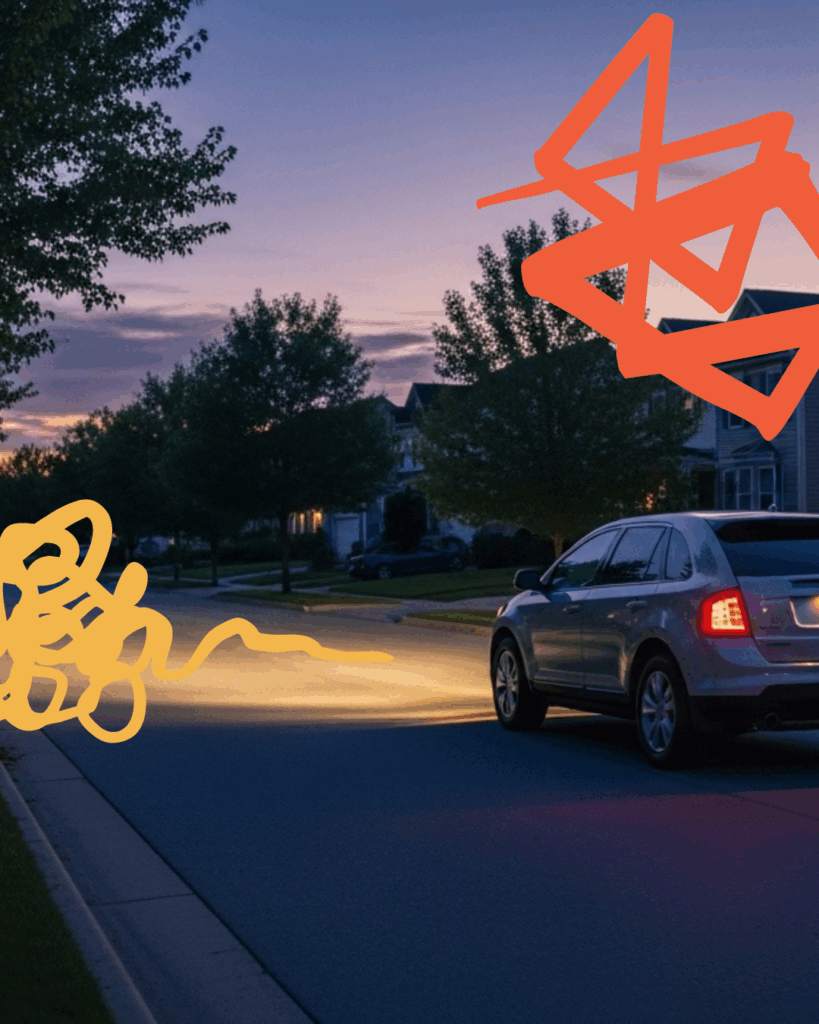

Lately, on the drive to and from my kids’ junior high, we’ve all noticed the same thing: the daylight is disappearing. My kids have reached the age where they notice it too, announcing at least once a day for the past week, “Why is it already dark?” as if this is the first time they have experienced the time shift (although I do think some of my clocks are embarrassingly still set to March).

Most afternoons, I sit by the big window in my house and complete my clinical notes. I watch the disheveled elementary school crowd trudging home from the bus around 3:55 p.m. It’s practically dusk. This brings me back to my own childhood tennis lessons—indoors for fall and winter—where I’d walk outside after class and discover it was already pitch black. I remember standing in the parking lot with my racket bag thinking, Where am I?

If you experience a drop in mood this time of year, you are, clinically speaking, completely normal. Therapists everywhere notice the same seasonal migration: our schedules become fuller as the temperature drops and the darkness creeps earlier into the afternoon.

This is because humans are mammals (surprise), and while we don’t hibernate, our brains and bodies still react to seasonal changes.

Many clinics are now promoting pre-seasonal affective disorder (SAD) interventions — basically helping people get ahead of the slump before it hits.

Instagram adds its usual flair with advice like: dip in stream water with ice chunks floating by, hold your breath for 30 minutes, sip something that tastes like vinegary death, all while sporting Patagonia’s latest puffy jacket.

All well-intentioned… but what actually works?

Research is remarkably consistent: winter changes the brain. Shorter days disrupt the body’s circadian rhythm, which leads to increased fatigue, lower energy, and mood disturbances because the biological clock simply gets confused. Darkness also influences melatonin levels, and when melatonin increases, sleepiness does too, which is why your body starts whispering “bedtime” at 4:00 p.m. Sunlight plays a key role in regulating serotonin, so when winter limits that exposure, serotonin activity drops and mood can follow.

Geography adds yet another layer. The farther you live from the equator, the higher your risk for SAD. Utah gets cold, but at least there’s sunshine. My brother lived in Michigan for a decade and described winter there as “gray from October to April, sometimes longer,” which, clinically speaking, is not ideal for anyone hoping to stay awake during winter.

Recently, I’ve been taking my dogs for early morning walks a few times a week. My alternative is going to the gym, where I always feel like someone is about to say, “Ma’am, the bathrooms are for customers only.”

As I navigate a room full of extremely sculpted fitness influencers (and people who look like their diet is a daily slab of steak with a side of protein powder) I often feel like the awkward extra in someone else’s highlight reel. Despite the mild disappointment that my walk won’t give me muscle definition on my back, I notice how much better I feel.

But here’s the thing: morning light exposure is one of the most evidence-supported interventions for SAD.

Resetting your circadian rhythm with early daylight boosts serotonin and stabilizes sleep.

And I do notice the difference—despite tripping over my dogs repeatedly because it’s still semi-dark.

Choose the strategies that fit your life, but research actually does support: morning light exposure, regular movement, consistent sleep cycles, social connection, and getting outdoors when possible. But you knew all that.

Most importantly:

It’s not a character flaw if you have a lower mood in the winter.

It’s neurobiology. It’s circadian science. It’s environmental.

You’re not failing — your brain is adapting to a seasonal reality.

Most mammals are literally sleeping through winter.

Meanwhile, humans are expected to finish end of year deadlines and quotas, host holiday gatherings, and produce beautifully wrapped presents while the rest of the mammalian world is literally not getting out of bed.

Give yourself some compassion this season. Your brain is doing its best with the amount of sunlight available.

’Til next time.